Our Problems Are Our Solutions.

As I continue to teach and lecture among my colleagues around the world, I have become increasingly aware that most psychotherapists train and practice within a paradigm that sees patients’ problems as rooted in pathology. These therapists wait and watch for a symptom to see how it might fit into a a category of identified disorders. That neatly solves the problem for the therapists, but not for the patients.

For nearly four decades, I have sat and listened to people who present their stories and their anguish. I still marvel at how unique are many of their problems and how well these problems also function as solutions. The more I explore a situation to find out what is right rather than what is wrong about it, the more creativity I discover and the deeper is my conviction that the human spirit is way ahead of the human mind in its genius for adaptation.

While an understanding of the science of psychology is the accepted basis for treating patients, a wider appreciation of the human spirit informs my practice. A therapist’s job may be less to cure a problem than to identify, respect and even revere how it solves or rectifies life’s dilemmas. And whenever I am able to cast a so-called problem in a positive light, the person gains a reinforced respect for himself and for what his or her spirit is seeking to achieve. And so do I.

Much of the satisfaction from my work is the inspiration I derive from seeing over and over again how imaginatively and often unwittingly we address each other’s fears, loyalties and love. Therapy, then, is as much about decoding the soul of a relationship as it is understanding the mind. Only then can it achieve reverence for the power of creativity of the human spirit.

More than any other case in my years of practice, Nancy and Steven Bembridge illustrates this.

Opening my office door to greet them, I was struck by their image, perched in the center of the waiting room bench, their hips, thighs and knees glued together.

On my office sofa they seemed to press even closer.

When asked about their visit, Nancy replied, “We went to an agency to adopt a baby and they said no. Well, actually, they said maybe we should see someone before we adopted.”

“Why do you think they suggested counseling?” I asked.

“Well, it isn’t because we don’t have a nice home. We have a good income and we have good backgrounds,” she said convincingly, as her list continued, but with a certitude, I realized, not intended for me but for Steven.

“So, how did they explain why they wanted you to come here first?” I asked.

“Well,” she said, staring into her husband’s eyes. “We’ve been married six years and,” and now with her eyes cast down, “haven’t had sexual intercourse.”

For a second I had to check my reaction. But the shock of their confession was mitigated by the image of them sitting together. How could they have sex? They were stuck together–fused–hip to hip.

I knew I had to somehow understand the meaning of their fusion. If I could discover what was behind it, I could understand what their sexual abstinence was a solution to. It was 1976, when I and other family therapists experimented with pioneering approaches that have now become the norm. But what I next did with the Bembridges could have jeopardized my career.

I rose from my seat and went over to them. “Adopt me,” I said and pried them apart to sit between them on the sofa.

They froze, yet a flicker in their their body language reassured me I had decided correctly despite what next happened.

Steven clenched his fist. “How can you do this?” he demanded, before stomping to the door. Nancy began to weep and followed him as if tethered. “We came here for help,” Steven shouted.

I trusted my instincts and curled up on the couch and keened in my most supplicant voice: “You’re abandoning me. You haven’t even adopted me and you’re abandoning me.”

The room spun on my words.

The Bembridges became statues. The echo of “abandoning” me hung like smoked trapped in a jar. After heart-stopping seconds, Steven’s upper body trembled and he crumbled into sobs.

Somehow “abandoning me” had struck him in the heart.

Nancy looked at me. I stood. She escorted her husband back to the couch and I returned to my chair. They resumed their welded position. The moment of magic was over and the work about to begin. I waited for one of them to speak.

Eventually, Steven started speaking through his tears: semenax and research

“As an infant, I was left on the steps of St. Leonard’s Church, in a basket. Nuns at the orphanage always told me it was a basket with a blue blanket. The nuns took care of me into high school.”

As he recounted his upbringing in the orphanage, not an uncommon experience in the 1950s, Steven sat erect, hands on his knees, eyes cast downward, occasionally glancing up and into Nancy’s eyes.

“I was lucky,” he insisted. “I was taught how to live a good life and I got a good start.” Steven continued to talk about his upbringing as sorrow filled his voice.

I asked how he and Nancy met.

“We met at a church party.” he replied, with a growing smile. “I saw it right away. She was everything I imagined a woman could be. Meeting her, knowing her, falling in love, I thought I found everything I missed. In her I found everything I lost. I got it all back. She seemed to be perfect.”

He went on extolling Nancy.

Nancy described her childhood, one of responsibility.

“Mom and Dad worked all day and that meant somebody had to take care of the house. I’m the oldest, so I got used to taking care of the three younger kids,” she said.

She then explained how she took care of Steven. “Whatever I did for him, he appreciated. He was so sweet.” She grinned at Steven and went on talking about everything from how she cooked his favorite dinners to doing his laundry.

I sat in wonderment. What was first deemed a problem–by the adoption agency–was actually an extraordinary solution.

I carefully chose my response. “It’s hard to put into words the respect I feel for you both and for the extraordinary union you’ve created. Yours appears to be a higher-order marriage than most. Sadly, you’ve been made to feel wrong for having been married all these years without consummating the marriage, but I think you’ve been misunderstood.”

They had sacrificed their sexuality to take care of each others’ needs.

I looked at Steven. “As you said yourself, in Nancy you have regained everything you lost, found everything you longed for. Clearly, she is more than a woman to you, more than a wife. In fact, she’s a madonna.”

Steve grinned in agreement. I looked at Nancy.

“And you found in Steven a child of your own, a son you could care for in exactly the ways you learned in your own family, exactly the ways that made you feel needed and fulfilled. Plus, he gives you love openly and willingly in return for your care. He is your perfect child. This is a beautiful, totally unselfish arrangement. Your love transcends the way we usually think of marriage.”

I continued. “I understand why you would not have intercourse. It would be a violation of a sacred, silent pact you made with each other. It would jeopardize everything. Steven, if you would have sex with Nancy, she would become an ordinary woman, less than your madonna, and you would be in danger of losing everything you had regained.”

I turned to Nancy.

“Nancy, if you have sex with Steven he would become an ordinary man, and you would lose the perfect son you found, the child who needs you so much. In a very real way, given the nature of your relationship, making love with him would amount to incest.” I went on solemnly. “Would a child change your marriage profoundly, irrevocably? Certainly. Maybe that’s another reason why you haven’t risked having a child.” I paused for a few moments to gather my “When it’s no longer in your best interests to act that way, maybe you’ll change your arrangement, whatever the risks.”

There was a church-like silence.

Nancy reached for Steven’s hand. “Thank you,” Steven said to me. “You put into words something that I knew in my soul, but strangely never recognized.”

“The price of change may be a costly one for you,” I said. “But you will know if and when you’re ready.”

They looked at each other and smiled.

“You are generous, caring people. I’m proud to have met you.” The three of us knew nothing more needed to be said and change rested squarely with them.

We shook hands knowing that in albeit fleetingly, we had grown fond of each other and were forever altered by our meeting.

They left just as glued together as they had arrived.

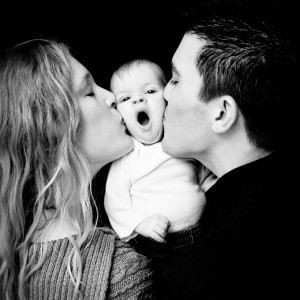

Two years later, I received a birth announcement for their son, Gerald Steven Bembridge.

First published on PsychologyToday.com on December 5, 2011.