When is sex bad for you?

When is sex bad for you?

Among mental health professionals, that question is hotly debated. Definitions of sexual pathology can range from sex that crosses legal lines to any form of sex involving humiliation or self-harm that leads to lowered self-esteem. And there’s just as much disagreement about what constitutes “compulsive” or “addictive” sex or even if such a phenomenon exists. Add to this ideas promulgated by religious groups in which transgressive sex is sinful even as a fantasy.

It’s no wonder most of us are confused about whether our own relationship to sex is “normal.”

Throughout history, the universal truths about sex have changed. Definitions of healthy sex have fluctuated. Homosexuality, once considered a perversion, was eliminated in 1973 from the list of psychiatric illnesses. Other categories of sexual behavior once considered deviant have undergone similar normalization as attitudes toward sex have changed. Up until the eighteenth century in the U.S., the age of sexual consent was 12, with between 16 and 18 now the ages, depending on the state.

Among professionals, the role that sexual fantasies play in our lives has also caused much disagreement. While sexual fantasies are now considered a universal experience, Freud and other early psychoanalysts believed that sexual fantasies resulted from feelings of deprivation in the absence of sexual satisfaction. Many experts still maintain this view, further reasoning that certain types of fantasies are signs of psychopathology. For them, a fantasy involving a patient’s sexual submissiveness, for instance, is viewed as a deeper symptom of “masochism.”

Some psychotherapists, sexologists and religious counselors say sexual fantasies should never be acted out because such activity might serve as a stepping stone to pathological, antisocial or even violent behavior. According to this theory, a wide range of sexual fantasies exist that fall outside of a set standard of normalcy. But, in fact, there is no scientific evidence to support the notion that acting out fantasies will lead to violent or perverse behavior the way substance abuse may lead to addiction.

My thinking about “bad” sex vastly differs from most of these points of view.

Our sexual fantasies and desires reflect our unique histories and are as original and varied as we are as people. Far from pathological or random, they represent subconscious attempts to heal unresolved childhood conflicts or satisfy unmet needs. Our desires and fantasies have meaning and purpose that, once decoded, then can safely and intelligently be used to create a satisfying and healthy sexual life.

If we can achieve authenticity by aligning our sexual behavior with our fantasies and desires, we can permanently change our relationship to ourselves and satisfy a host of deeper needs. We can reclaim rejected, repressed or abandoned parts of ourselves and integrate them into our being, which is so crucial to our health. By challenging cultural values and norms, we will arrive at our own set of moral values and obligations that derive from self-knowledge and self-acceptance.

Embracing our sexual truth reverses the corrosive influences of guilt and shame, and enhances our sense of self-worth. By honoring our fantasies and desires, we do not deny the dark and difficult aspects of it.

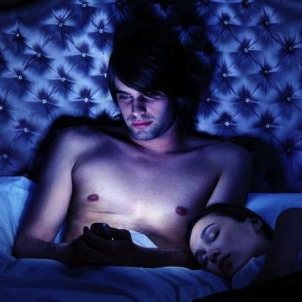

Sex can turn bad for us when we repeatedly pursue encounters with the hope that each new experience will relieve our tension, anxiety or boredom or help us escape from pain or conflict. Because our body produces a surge of powerful chemicals during the excitement of sex, binging acts as a momentary antidepressant blotting out pain and flooding us with feelings of well-being. But when the effect begins to wear off, we are left with even greater anxiety, feelings of emptiness or shame from which we also crave to escape. The thought and pursuit of sex progressively dominate our lives until we are caught up in a cycle of endless lust or romantic obsession.

Every compulsion has a healthy intentionâwe enact rituals in an effort to soothe pain or conflictsâbut the anarchy of compulsive lust leads to meaningless or reckless sex, or sometimes its opposite, sexual starvation. Without making a conscious attempt to understand the true nature of our sexuality and it’s meaning and purpose in our lives, we cannot direct our energy towards healing. Compulsive acting-out indulges selfishness and self-loathing, where smart sex generates self-love and generosity.

My patient Jennifer knew exactly what excited her. It wasn’t something to which she gave much thought, she simply acted it out. Jennifer was always attracted to risk and danger and never wanted to know why or what her preferences meant. “That would have spoiled the thrill,” she told me in hindsight.

By the time Jennifer came to therapy, she had already admitted that her sexual activities had grown beyond her control. The fact that she was married with two children hadn’t stopped her from secretly seeking sex with strangers. But when she found herself obsessively thinking about prostitution, she finally decided it was time to look for help. Until that point, her personal life had been geared around how and with whom she would next have sex. As soon as she finished one encounter, she was thinking about the next.

And surprisingly, no one suspected.

“I was already having sex with strangers, why not get paid for it? That’s how out of control I got,” Jennifer said. “I finally realized, this has got to end. Is this what I want my life to amount to? I’m a 35-year-old whore cheating on my husband. I can’t even let myself think about the kids. I was constantly afraid of being caught. That’s when I made the decision to stop.”

A year before she came for therapy, Jennifer had gone on the Internet and found a Sexual Compulsive Anonymous group that met during the afternoons when her husband was at work and she was at her most vulnerable. She began attending meetings several times a week.

After a few months, with the support of her group, Jennifer made the decision to come clean with her husband. She felt she had to take responsibility for her behavior. It was also the first time in her life that she had ever taken her behavior so seriously.

Her husband was both blindsided and devastated. He had no idea that Jennifer had a double life. He felt angry and betrayed. At first, he asked her to move out of the house bad credit history payday loans, but not wanting to disrupt the children’s lives, he settled for her sleeping in the guest room. He refused to move out of their bed or speak to her unless it was about the children.

“I’ll never forget the look on Michael’s face. He was broken,” she said, her own face ashen as she recalled the conversation.

Somehow they survived the next six months. Jennifer faithfully attended SCA meetings. For the first time, she stopped keeping secrets and along with a deep feelings of shame, she also felt a sense of relief.

It had been an extraordinarily painful year for both her and Michael. Yet on the first anniversary of her sexual sobriety, to her surprise, Michael told her that though he would never forget the pain she caused him, he admired her determination to live a healthy life. He said he didn’t know if he could ever fully trust her again, but he wanted to try. They both wept and for the first time since her disclosure, they slept in the same bed.

But the more things improved with Michael, the more inexplicably sad she felt. She made another decisionâto come to therapy to “finally face all the demons.” When I asked her what that meant to her, she bowed her head and look directly at the floor. After a few moments of silence, she began her devastating story which she had told only one time before.

Jennifer and her two younger brothers were raised in a middle-class suburb of Detroit by her mother and stepfather. Her parents had divorced when she was six and within a year her mother remarried her high school sweetheart and her father’s best friend. She was nine when, while watching television on the living room couch while her mother worked the night shift, her stepfather ask her to massage his shoulder which he said he injured at work. He had asked her before, but always in her mother’s presence. She always took pleasure in the idea of pleasing him, and with her brothers sitting nearby, she thought nothing of it.

Later that evening, after her brothers were in their beds and she in her own, her stepfather came to her room to thank her. He sat on the edge of her bed, brushed her hair with his hand and gently kissed her on the cheek. Then, he placed his lips on her mouth and kissed her again. Though he left her room immediately after, in that instant her life changed.

Several nights later he returned to her room and instructed her to massage his chest. He removed his shirt and asked her to rub the lotion he had brought with him across his body. Within a short time, he pushed her small hand toward his penis and held it there.

His nighttime visits continued regularly and soon he was placing her face down on her bed, talking her clothes off and rubbing his body against her, until one night he raped her. “I was terrified. I never said a word. He told me that If I told anyone that he would tell them that I had made it up. No one would believe me,” Jennifer said.

The rapes went on for several years, sometimes more than once a week. Finally, on the day of her thirteenth birthday, she gathered her courage and told her mother that her step-father was having sex with her. Her mother was shocked and devastated. Without hesitation, she called the police and when her husband returned from work he was confronted and arrested. The marriage ended right then.

Like most abuse victims, it was impossible for Jennifer to make sense of all the conflicting feelings of anger, shame, guilt, love, pain and fear that occurred during and after her sexual abuse. As she entered puberty and developed physically, she became even more confused. Now she had sexual feelings, but along with them, associations that frightened her: She could not stop fantasizing about her stepfather. She imagined having vaginal intercourse with him, a thought which she found both horrifying and pleasurable.

By the time she was sixteen, she was having regular sex with older boys and men. She felt powerful knowing she could please them. She was struggling to gain control over the pain and indignity by unconsciously acting out a more pleasurable version of her abuse. But because the meaning and purpose of her fantasies and behavior were not part of her consciousness, they could not produce true healing. Instead, compulsive sex produced a numbing, narcotic-like effect, which, for a time, served its purpose.

Now, twenty years after her abuse ended, she was finally dealing with those feelings rather than escaping from them. As we discussed the details of her trauma in therapy, she recognized that her childhood was stolen from her and could never be replaced. Soon she plunged into a period of genuine grief. Never before had she felt safe enough to allow such feelings and now that she had, she didn’t think she would ever stop feeling sad.

I invited Michael to the next session on the hunch that her experience would widen his understanding and, at the very least, foster compassion. I was right.

As the deepest mourning lifted, anger replaced it. She began having fantasies of getting even with her step-father. At the time of his arrest, her mother had been advised not to prosecute her husband because the events surrounding a trial would further traumatize Jennifer. Now Jennifer felt outraged and wanted to punish him.

During this stage, Michael and I bore witness to her story. Along with her SCA group, we supported her through each twist and turn of her grief over the period of a year.

The restorative powers of mourning are extraordinary. When the process is fully embraced, it runs its course and leaves room for a new perspective. And while life challenges can reawaken some aspect of the trauma, its affects grows less powerful with time. Eventually, the pain is left in the past and the task of rebuilding life in the present takes priority. Jennifer’s courage paid off. She is finally prepared now to follow the steps of Intelligent Lust and establish a sexuality that is separate and free from the trauma.

First published on PsychologyToday.com on November 14, 2011.

1 comment

Tegan says:

Jun 14, 2012

Wow that touched me and opened my eyes a lot more than before. I am so sorry that you had to go through that. May God bless you and may you have a wonderful life. Well I know what its like to be raped but not by a parent. My “best friend” at the time took advantage of me in my weakest time. I told him to stop and I kicked and screamed but he didn’t stop. He was drunk but I will never forgive him. I am now in a happy relationship but I have not told him about that night. If I did would he believe me or would he be ashamed to date me?? For me its in my past and forgotten and I don’t want to relive it again. Thank you for moving on and being strong. Enjoy a wonderful life now.